Awareness

A First Step Toward a Framework

Written by: gibru

Published on November 30, 2022

Updated on August 14, 2025

Introduction

This piece of writing is an invitation to play a game. A linguistic one to be precise. Or maybe just something a bit different. Who knows? Of course, there’s nothing prescriptive about this little endeavor. Basically, this ain’t about telling you how to perceive language, but to inspire you to think about its building blocks. You know…those components that we seem to be taking for granted far too often.

Let’s start with awareness. To me, it is a fascinating concept — worthy of exploration. But where to begin? We could, for instance, get an idea for what it means by looking up one (opens in a new tab) of its dictionary definitions:

The state or level of consciousness where sense data can be confirmed by an observer.

Linguistically a bit too dense, isn’t it? Not to mention that we probably would have to look up the definitions of state, level, consciousness etc. to make sure that we truly understand the result of that linguistic equation. Obviously, you can imagine what follows after looking up those definitions. Fun times! But in case you feel excluded from the party: take a dictionary definition of the word word (opens in a new tab):

A sound or a combination of sounds, or its representation in writing or printing, that symbolizes and communicates a meaning and may consist of a single morpheme or of a combination of morphemes.

First things first, whether we agree with this definition or even understand it to begin with doesn’t matter. I just grabbed the first one I could get my hands on as it meets my only requirement: it contains a bunch of words. Or, in other words (pun intended): we are using the thing to be explained to explain the thing to be explained. As I said, fun times…

Another option would be to get a more nuanced grasp by taking a look at how it evolved as a concept in different contexts (opens in a new tab). Basically, we define categories, label them, identify with the label and say things such as: In neuroscience, we define awareness as… — which brings me to a quick question: do you have time to become a scholar? Not to mention that the level of complexity we’d encounter there would probably cause a short circuit in our cognitive realm.

Personally, I like a more playful approach. For instance, we could put awareness under a microscope to get a closer look at its conceptual components. Of course, the idea isn’t to reinvent the wheel, but to rearrange its building blocks in a slightly different fashion. But don’t be fooled: the end result won’t be yet another definition to be adopted by a speech community (opens in a new tab). Instead, we’ll probably end up with some sort of framework.

Inspecting a Concept

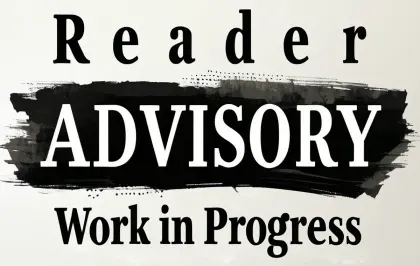

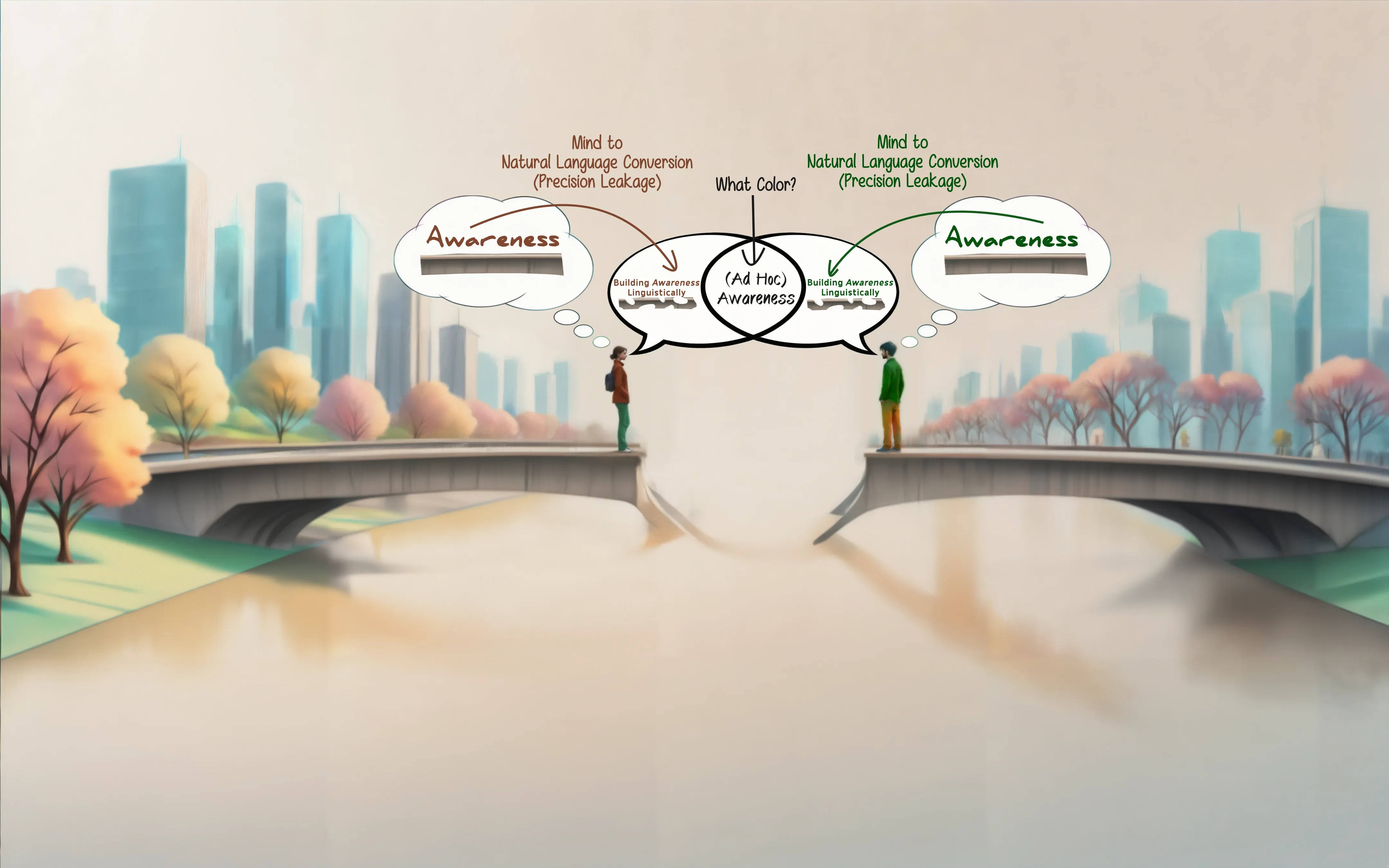

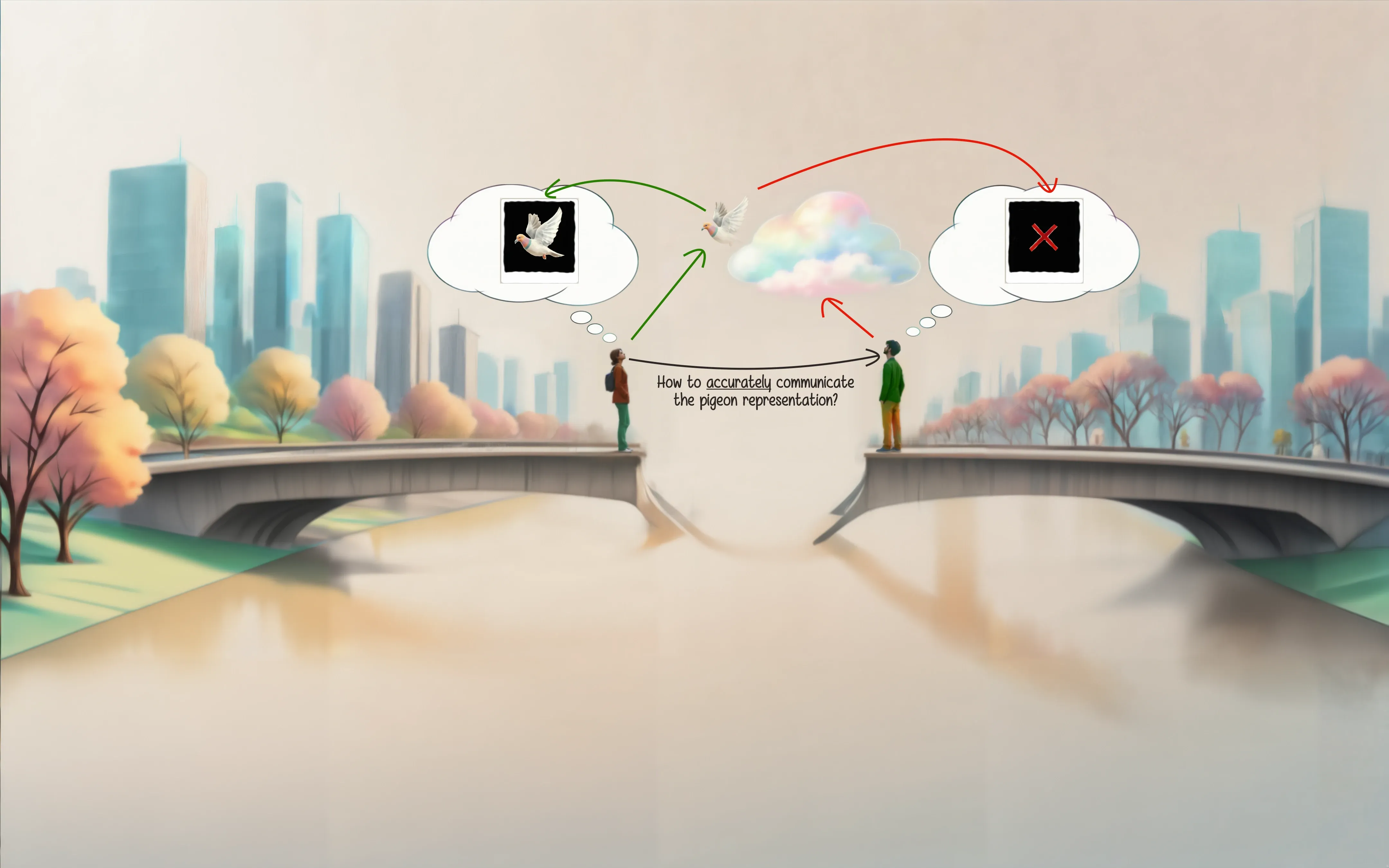

Consider the following illustration:

Codifying Nuances of Meaning in Color

Being born into, growing up with and living inside any natural language (opens in a new tab) (e.g. English) can easily trick us into thinking that we know how to understand whatever we’re exposed to in that particular language. We set up arbitrary levels of linguistic mastery from native speaker to can’t-put-a-sentence-together and judge fluency, validity and other criteria like there’s no tomorrow. But I’m suspicious: while we could endlessly philosophize about the nature and meaning of anything and everything, I’d rather not. Instead, I’d like to look at language as a playground or a laboratory: like the chemist who is synthesizing chemical compounds, the physicist who is splitting atoms, or the pedant who is splitting hairs, the wordsmith is synthesizing thoughts and splitting sequences of letters. Or, in a nutshell, experimenting with carriers of meaning. Whatever that’s supposed to mean.

Fig. 1 depicts a small challenge in a somewhat simplified form: to find a common denominator for communication. Depending on the context, the meaning of a word can actually vary to a degree that makes it rather difficult to communicate with each other — something that is often overlooked by people who belong to the same natural language group. Speakers (especially highly proficient ones) of a given language assume they understand one another by default. As a matter of fact, it isn’t uncommon to think that we have a linguistic common ground just by belonging to the same language group — until our verbal exchanges become complicated. And when linguistic matters meet complexity, we tend to inject emotion rather than attempting to solve the puzzle. Because, really, that’s all it is: a puzzle seasoned with a bit of emotion here and there. And sure, that might sound a tad simplistic, but remember: this piece is nothing but an invitation to play a game.

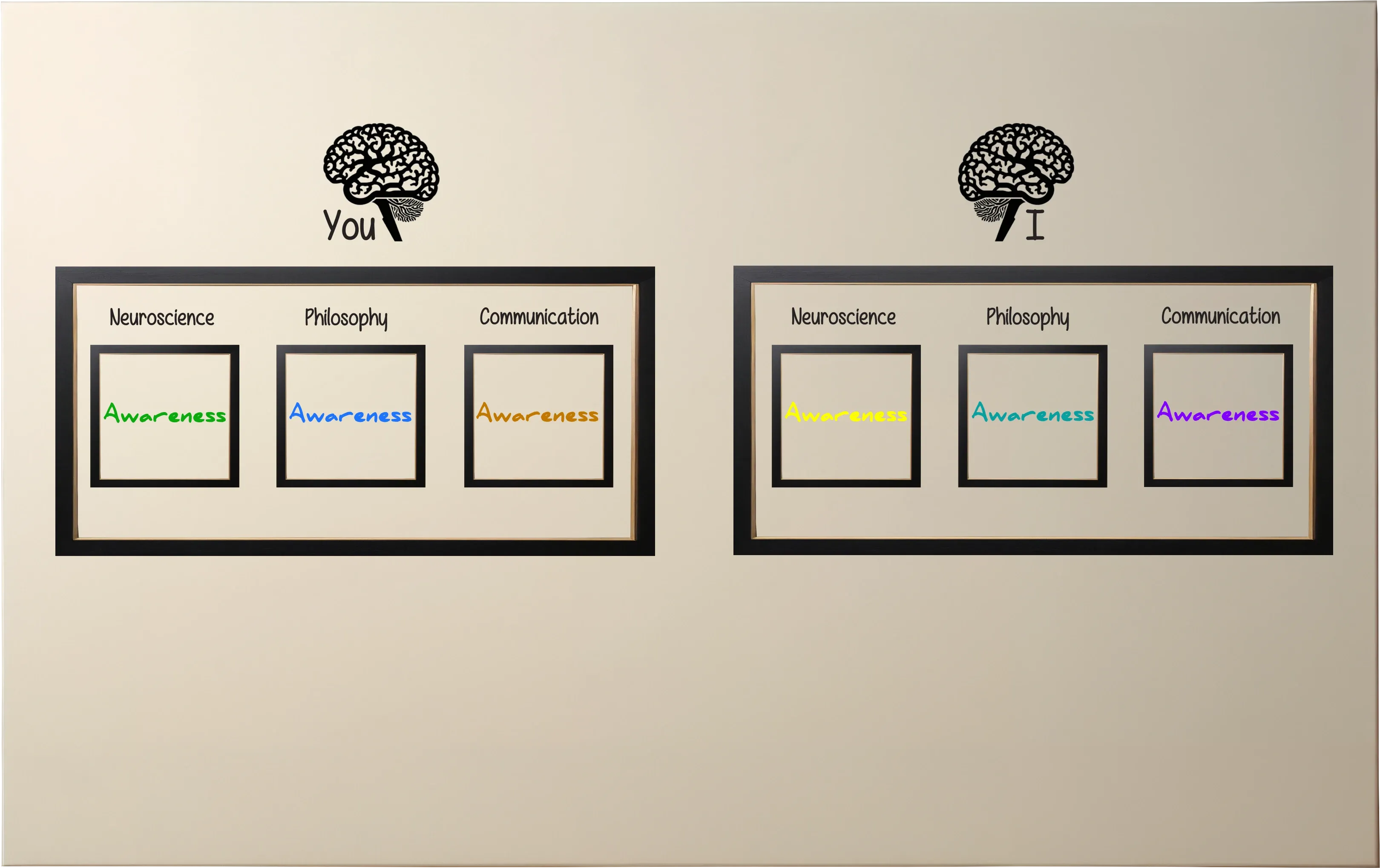

Now, on the surface a concept could look as simple as this:

From Bricks to Wall

Not sure about you, but I have no idea how we go from a bunch of bricks to a wall. Of course, we could set up a couple of rules such as a minimum amount of required bricks and a particular way to stack them on top of each other, but that seems rather arbitrary, doesn’t it? Also, it lacks context. And that context can be tangible such as a house with the wall being a part of it — or it can be conceptual such as a marker of a separation with the intention to keep others on one or the other side of it. And those are just a few ideas already adding a ton of cruft to the concept of a wall. In other words, plenty of room to disagree and argue regarding the exact moment a bunch of bricks can be called a wall.

But here’s the thing: the brick/wall question isn’t new. A couple of weeks after creating Fig. 2 I somewhat serendipitously discovered the sorites paradox (opens in a new tab) while researching something completely unrelated. Here’s the paradox in a nutshell:

If a heap is reduced by a single grain at a time, the question is: at what exact point does it cease to be considered a heap?

So whether we call it bricks/wall or grains/heap, the song remains the same. It shouldn’t even come as a surprise if this same observation has been made countless other times in the past. And we probably haven’t seen the last of it in the present and future — simply worded differently. We tend to repeat what has been said not just because we simply want to regurgitate other people’s observations — but because certain things will become obvious to us independently of one another. That’s probably a good reason to take a closer look. Come to think of it, Fig. 2 and other observations like it are fairly obvious linguistic conundrums, yet convenient to ignore.

That said, please forgive me for being obvious or unoriginal: I’m not trying to add yet another new observation to an existing pile of superficially explored ideas, but to connect the dots between the original observations put forward and encoded into language by thinkers before my time. And I’d like to make sense of the languages that have been uploaded into my cognitive realm without my permission. Speaking of…have you ever wondered how that’s even possible? Does what I just called cognitive realm depend on language? Is it built with it? If so, what does that mean for exploration? I suggest that you keep that thought in mind as it makes for an interesting riddle.

By the way, the reason I used the word serendipitously earlier on is simply to express a feeling: I had unexpectedly stumbled upon something useful for this piece of writing and it felt good. Imagine: if I weren’t aware of the existence of the sorites paradox, we might have a completely different foundation for conversation. The context would be completely different, affecting the meaning of individual building blocks. For instance, you might want to ask me if I was inspired by the paradox to come up with my brick/wall example. The answer’s no. Of course, if I were exposed to the sorites paradox before creating Fig. 2, I might have never thought of the brick/wall example to begin with. Maybe. Who knows? Doesn’t matter. Just a thought.

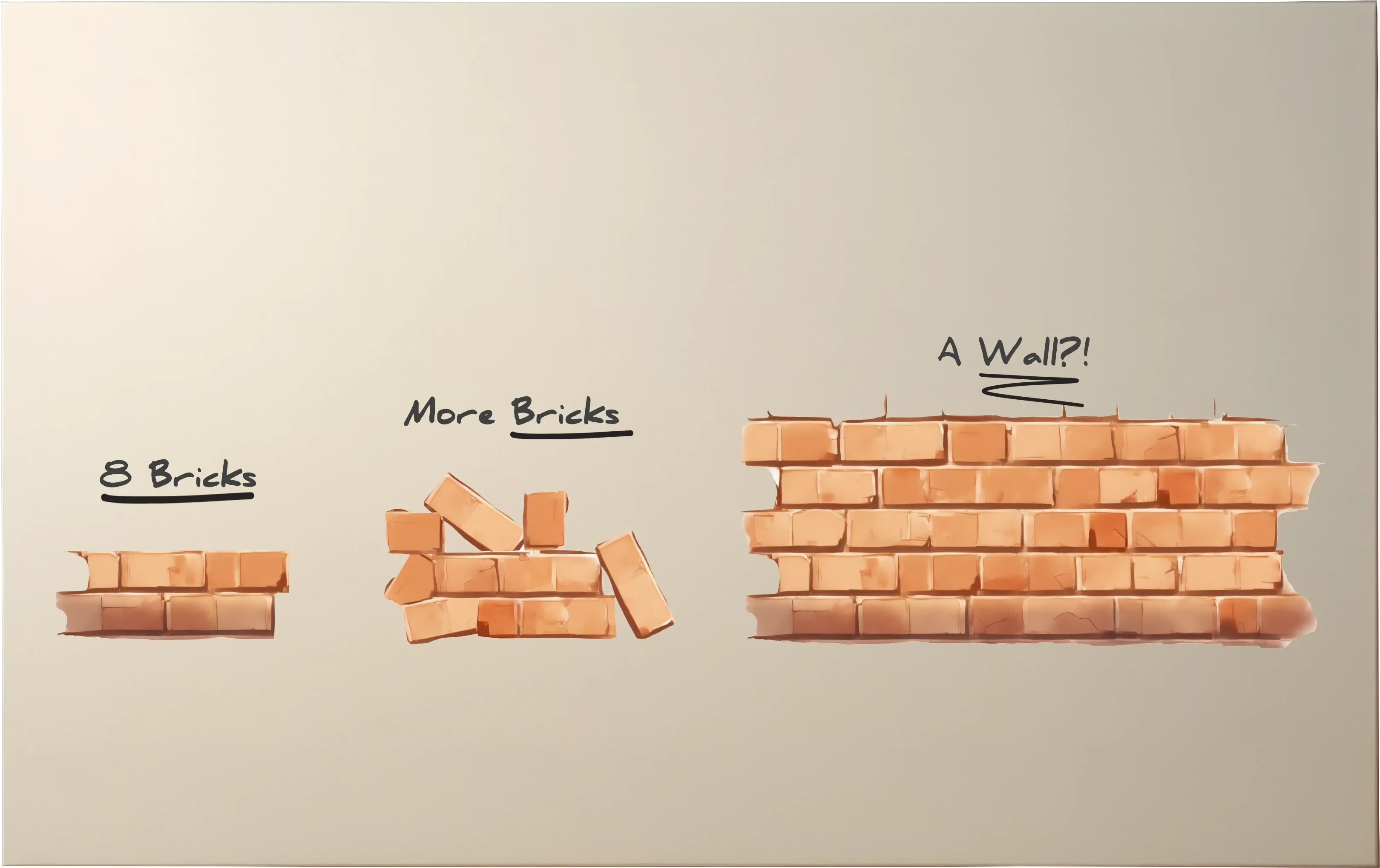

At any rate, the reason I have decided to include my awareness of the sorites paradox is because I’m interested in the underlying conceptual foundation shared by my brick/wall depiction and the aforementioned paradox. As a matter of fact, I was never interested in trying to answer the question itself, but to use the conundrum as a conceptual tool to help set up this little game of mine. Here’s what I mean by that: the metaphor used in Fig. 2 doesn’t really translate into building a concept such as awareness. Instead, it can be combined with Fig. 1 to stretch the boundaries of natural language as a tool to express ourselves:

From Bricks to Wall

While combing visual metaphors won’t magically reduce complexity, it can make it more apparent. And that’s what I’m really after. Think of it this way: using a tool to help us deal with the complexity of a problem doesn’t reduce the complexity of the problem itself. Instead, it can improve our ability to deal with that problem. The main requirement: we first have to learn how to use the tool — and, let’s face it, the learning process could end up being complex itself. Bit of a bummer, ain’t it? Why does everything have to be so complicated? Well, I don’t know about you, but I’m cool with that. Gives us something to break down into smaller and less complex pieces. Moving on.

Approaching a concept as depicted in Fig. 2 leads us to assume that we share an identical understanding of the same words. Put simply, imagine that each of one us is building that wall with identical bricks — with brick being a metaphor for word. These bricks come in the exact same atomic structure and there’s only one way to stack them on top of each other. All we gotta do is decide what precise moment can we call our construct a wall. Same with awareness, right? You know…when you’re aware of something. A piece of information stored in our mind and retrievable. Or whatever. And boom! We have a precise moment that turns awareness from a simple brick into a wall.

Within that scenario, Fig. 1 unfortunately loses its colors as a consequence of our obviously shared understanding of anything and everything. After all, we are using the same building blocks to build these concepts in our mind. There’s no need for colors anymore to distinguish between different perceptions of the awareness concept. I think. I mean…I assume. Well, let’s just say that’s what we like to believe and — in our defense — we somewhat have to. Otherwise, communicating with each other would be like solving a mathematical equation before every word we produce (maybe except for conjunctions (opens in a new tab)). But that’s not what we do. At least not consciously. Don’t have time for that. Besides, it’s not like you’ve just made an extra effort to understand words such as mind. Probably just took it for granted, didn’t you? Your mind is made of the exact same bricks as mine. That’s what you think, right? So when you make serious statements based on your understanding of the concept, you can simply assume that I’d agree because my perception is identical to yours. After all, we live in the same world, don’t we? Well, I’m just teasing so don’t worry. And to be honest, I’m guilty as charged as well. Even worse, I use a word such as mind in my writings and just assume it’s good enough to convey whatever is on my…oh well!

Unfortunately for us, that’s not even where the difficulty ends. While Fig. 2 conveniently assumes an inherent common ground for building concepts, Fig. 1 has its own issues as it bypasses the dynamic nature of language. In other words, if you show me your color and I show you mine, we can be sure that we share the same understanding — which is really just as simplistic as Fig. 2. But let’s break this down, shall we?

Applying the idea behind Fig. 1 to a verbal exchange leads to at least two shortcomings. The first one would block us in our path to communicate altogether:

This Bridge Doesn't Connect

This one is a little tough to explain, but basically: while we share a physical context (outside), we both have our own understanding of awareness — marked by different colors (as initially also illustrated in Fig. 1). The problem, however, is that the physical context isn’t precisely captured by the term outside. There are other things such as noises and smells, different colors we perceive etc. that all have an effect on us as we move along that bridge. So every instant has the potential to slightly alter the color of the bricks or building blocks used to construct our current snapshot of awareness and, thus, its color. In other words, we don’t simply store linguistic building blocks in our mind™ where they remain static until we retrieve them. Instead, these blocks affect one another and are in a dynamic relationship with whatever we experience, learn etc. — and that includes the act of communicating with one another. Put simply, as things stand right now, we won’t be able to meet on that bridge.

We could even imagine language as a seed that is planted in us. This happens as soon as we get exposed to our first linguistic building blocks. Combined, they slowly blossom into the mind™ and, throughout our life, they constantly evolve in a dynamic relationship between themselves and whatever we’re exposed to, culminating in an ever-changing sense of self.

At any rate, when it comes to a more in-depth explanation, I suggest that you let a computer do the math. Clearly, I’m not cut out for this. I know that’s a bit of a cop-out, but I’m not here to convince you of anything — just to make you think a little.

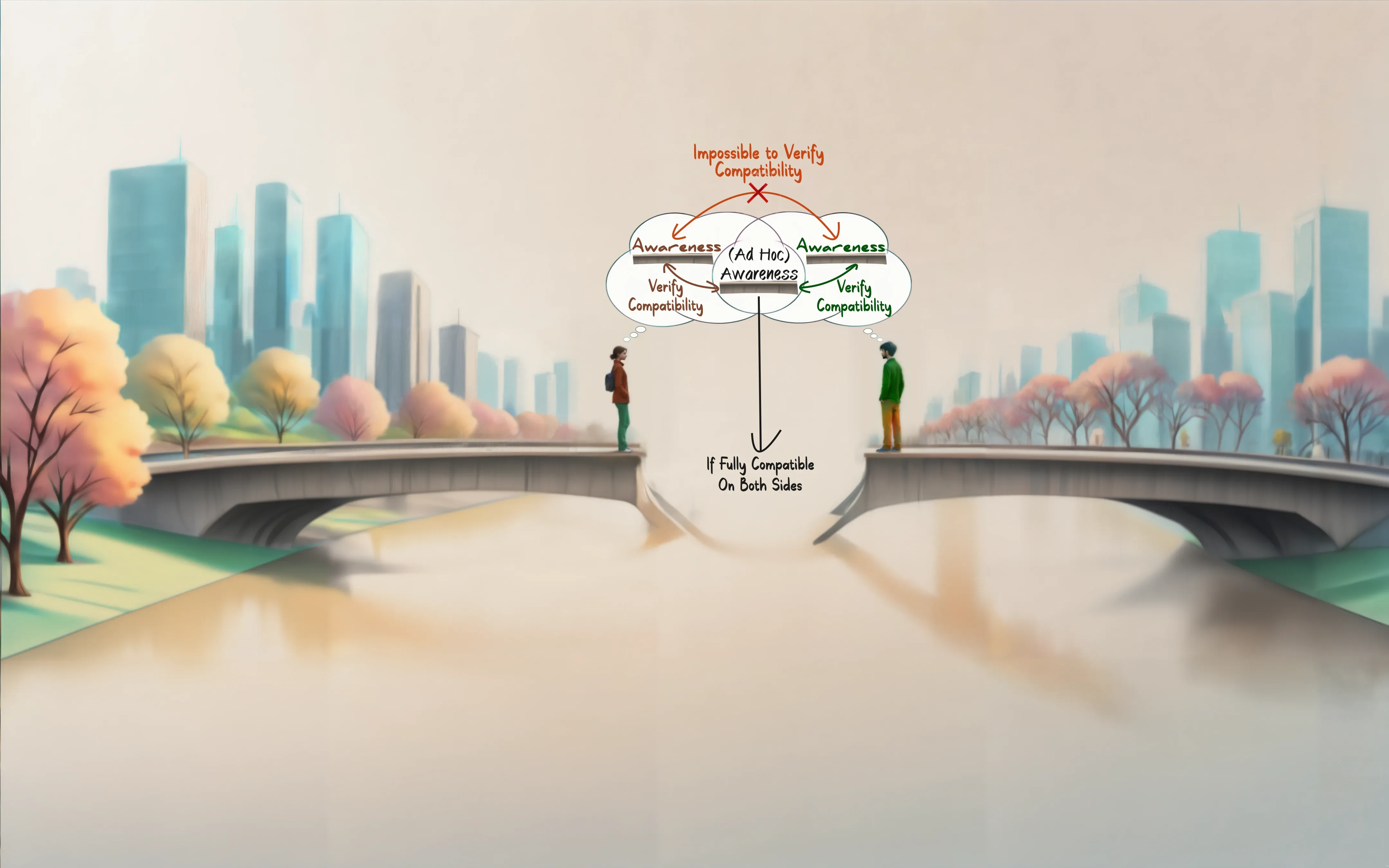

Now, what if we happen to be right in front of the gap with the other side at our fingertips? That would simply lead to the second shortcoming of Fig. 1:

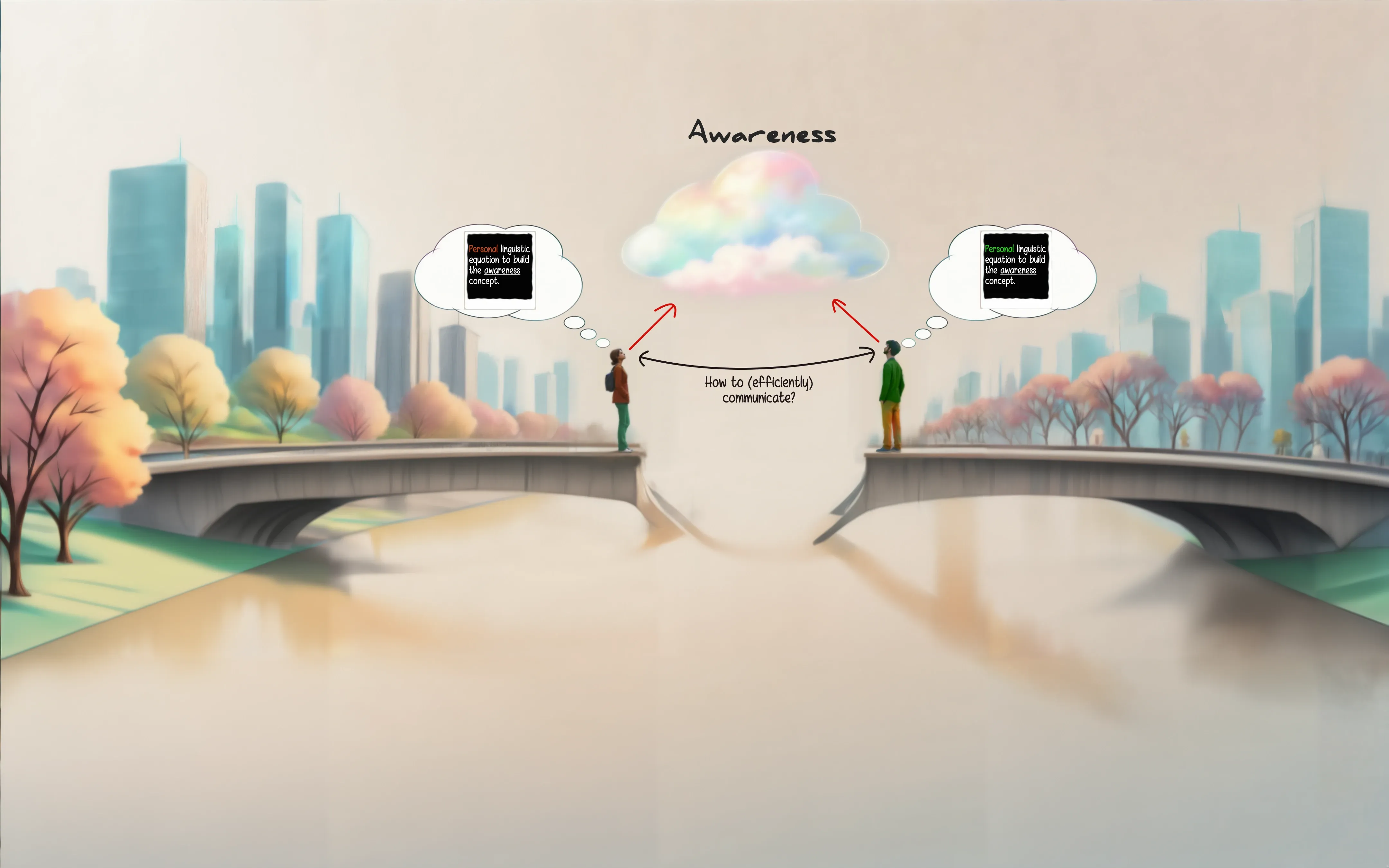

How to Bridge the Gap?

Imagine that there’s room for exactly one building block to bridge that gap so we can meet in the middle. Which one is it going to be: yours or mine? Well, that’s a bit of trick question, isn’t it? I mean, using either your block or mine would set us back to Fig. 4 where we keep walking and walking without ever getting closer to each other.

In Fig. 5, we now face the question asking how we could make sense of the other’s perception of a concept without having access to the identical resources to build that concept in the first place. There’s no way for me to know what exact color mixture you are using to colorize the concept nor would you know how I mix my colors. Something has to happen first. Something more dynamic.

One of the most overlooked difficulties when it comes to challenges such as the one depicted in Fig. 5 is asking questions that are actually answerable. And to make sense of those that are not. Here, we are not going to waste our time trying to figure out an answer. As far as I’m concerned, that would be completely pointless. Fig. 5 has done its job. It was supposed to make us think about the problem, not to provide us with an answer. For that, it is way too incomplete. However, in that incompleteness we find a hint that points us in a direction that allows us to move forward:

Meaning at the Intersection

Since we’re not (yet) mind™ readers, we somehow have to make our thoughts on awareness accessible to each other. For the sake of argument, let’s choose dialogue (opens in a new tab) as an approach to achieve this goal. Essentially, what we can do is to share a fraction of our (linguistic) building blocks to expose our conceptual understanding of awareness. This is the foundation for what I call

The challenge we face is that, in our mind, a concept may feel rather wholesome, but as soon as we convert it into natural language, we lose this wholesomeness i.e. we leak precision. This is what I’ve illustrated as a building block with holes. Such an incomplete building block would make for a rather shaky foundation by itself and very likely break down if we choose it as the foundation for our common ground.

With dialogue as an approach to this conundrum, we can create an ad hoc (opens in a new tab) meaning of awareness that only exists in the context of our little verbal exchange. Of course, sending linguistic building blocks back and forth will obviously have an impact on our current understanding of the concept. After all, the building process of the ad hoc meaning will automatically contribute to shaping our mind™. However, for the sake of argument, we are going to conveniently ignore that aspect because imprecision is part of our tool set — which brings us to an important thing to understand when it comes to precision leakage.

Let’s imagine our understanding of a concept such as awareness as an iceberg (opens in a new tab). The part that we are able to share with each other through some sort of dialogue is simply the tip of that iceberg. This is because natural language as a communication tool simply cannot account for the monumental complexity of our conceptual understanding. Anything converted into an expressive system will lose some of its details in the process — and yet, this incompleteness might just be enough of a contribution to build our ad hoc concept toward improved linguistic precision.

Basically, to appear to function in our daily lives it often doesn’t matter that we cannot reproduce linguistically what’s on our mind™ with complete accuracy. That is fine as we will see see later on. Moreover, natural language’s imprecise nature doesn’t stand in the way of progress — quite the opposite actually. Often times, it is precisely this imprecision that forces us to move forward. The real challenge has more to do with the finite resource at our disposal to solve these linguistic puzzles of the mind™: time. And, in this day and age, probably also our ability to deal with distractions.

At any rate, imprecision can sometimes be the result of a flaw in our approach — for instance in the form of an oversight. Or based on unawareness. However, at other times it can be a tool to get rid of the obstacles in our way forward. And if you are concerned with the question of figuring out when it is which, the answer will simply be a value judgment — which is of no use to me for this piece of writing. For our mission, we shall be concerned with usefulness instead…leading us back to ad hoc awareness and its purpose.

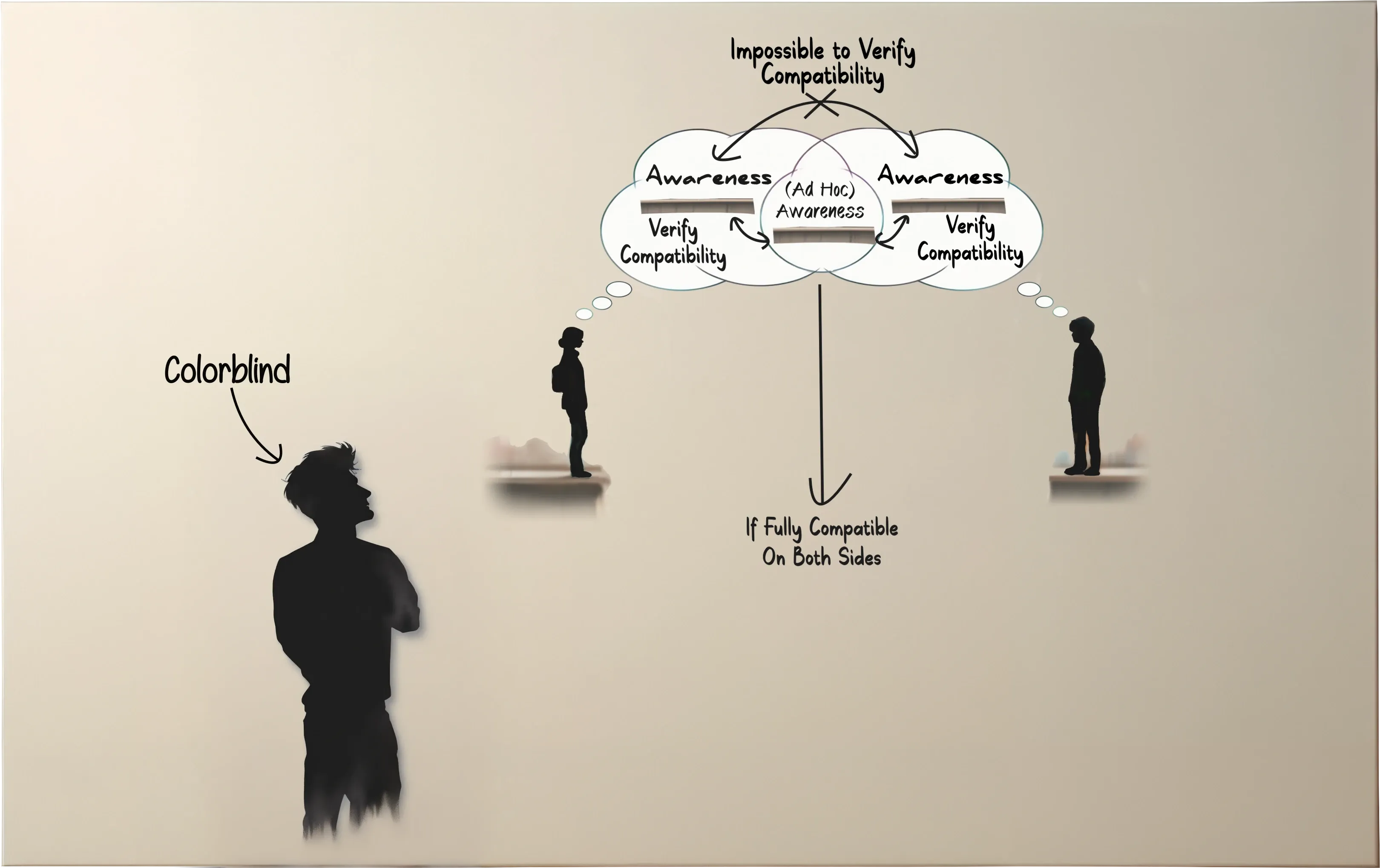

To keep it short and to the point: ad hoc awareness is a tool serving as an intermediary (opens in a new tab) to verify the compatibility between the ad hoc definition itself and our individual (current) understanding of awareness — and by extension between our shared perception of the concept:

Check for Compatibility

In Fig. 7 I have removed the speech bubbles to focus on how our dialogue created a kind of shared mind™ space — illustrated by the intersection of our mind™ bubbles. Essentially, the result of our dialog leads to a temporary shared mind™ space with ad hoc awareness at the center.

In order to be able to verify whether we are more or less on the same page when it comes to the meaning of awareness, we now have the option to verify whether our ad hoc definition of awareness is compatible with our own (current) understanding of the concept. So if we both end up with a compatible result between our shared ad hoc definition and our own understanding of the concept, we have a foundation for discussion — or food for thought.

What’s important to keep in mind™ is that an ad hoc meaning that is compatible for both of us doesn’t imply that we’ve built the concept with the exact same building blocks — it will always be an approximation, nothing more. Again, that’s absolutely fine as the current state of our species should prove: we do show incredible results based on a type of collaboration that can only be fuelled with an expressive system such as natural language.

That being said, something that can easily be confused with direct access to a shared ad hoc meaning is direct access to each other’s conceptual understanding. Again, I’m not aware of any mind™ reading capabilities. And frankly, even if we had them, I don’t think that, as humans, we’d have sufficient cognitive capacity to fully decode another person’s mind™. Come to think of it…probably including our own. In other words, in our current state of evolution, we’ll always have to negotiate for meaning — be that in our own mind™ or with anyone else capable of making sense of our expressive systems.

With all that in mind™, does it even matter whether we can share the exact same understanding of the concept awareness? If you think about it, coloring the word in one mind™ red(-ish) and in one green was an arbitrary decision of mine to get my point across. Why don’t I account for the option that we both might share the same color to begin with? Is it because I fail to imagine that possibility? You know, if I can’t imagine it, it cannot be possible. That sort of thing.

More importantly, however, what exactly are we supposed to do with the results?

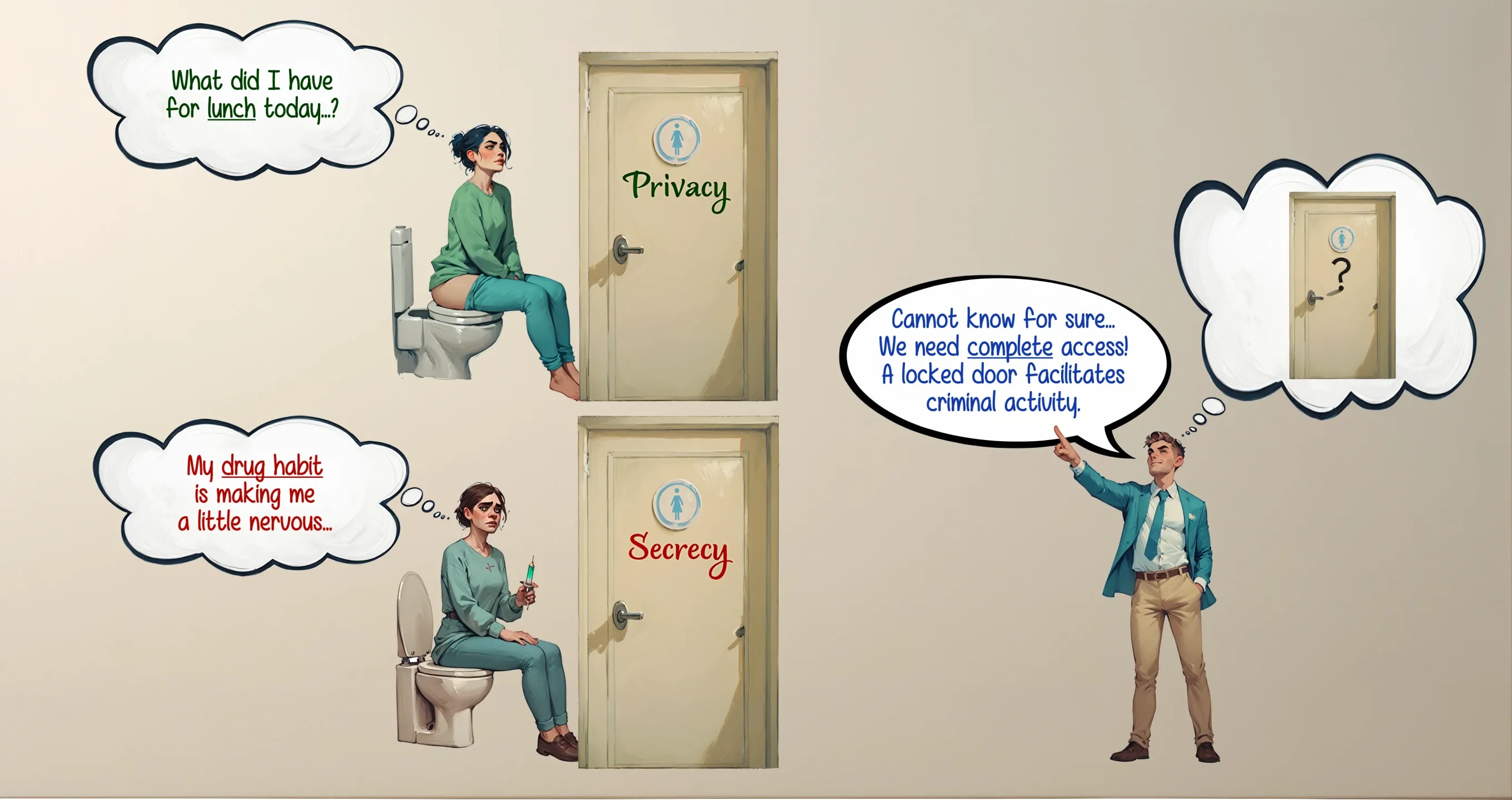

Locked Door Dilemma

The first thing to point out is that full compatibility doesn’t depend on high linguistic accuracy — nor does it require our conceptual understanding of awareness to be grounded in some sort of accepted reality by other people. As long as our ad hoc concept is compatible both with your understanding of awareness as well as mine, we’re ready to bridge that gap — regardless of whether we actually know what we’re talking about. Here’s an example using the privacy concept to make this a little less abstract:

You: Why don’t you care about your online privacy?

I: Because I’ve got nothing to hide.

You: Alright then, let’s have a look at your bank account.

I: Well, I might have nothing to hide, but I believe my wife does…

Our verbal exchange starts with (online) privacy as its conceptual foundation. But are we actually building an ad hoc definition for privacy?

Earlier on, I’ve mentioned that natural language isn’t always that precise to begin with — and that’s fine. However, by using our language to communicate with each other we also develop nuances that help us to express ourselves with an improved precision.

For instance, regarding privacy and as far as English is concerned, we do have such nuances already encoded in the language. Being aware of one such nuance in particular can help us detect whether we build our conceptual bridge for privacy — or for a different, albeit related, concept:

The Locked Door Dilemma

Fig. 8 depicts what I simply call the Locked Door Dilemma. Essentially, this is a visual metaphor or a tool to tease out a linguistic nuance: the difference between privacy and secrecy and why we could easily confuse the two. That confusion is, for instance, often used to trick people into making decisions against their own interests — such as an increase of a surveillance society.

Now, the challenge is to understand that both of these concepts, privacy and secrecy, can exist within the exact same context: behind a locked door. In order to identify which is which, we need something more — something that puts meaning into a dynamic state. Incidentally, this should make the point of Fig. 1 really obvious: context can have a huge influence on building meaning. So when people are asked to discard it when explaining something important, for instance, they might as well be asked to fabricate their stories from the ground up. Getting to the point ain’t as easy as the impatient want to make us believe.

Of course, as mentioned earlier, it is important to keep in mind™ that our language has to have these nuances encoded to begin with. Otherwise, no Locked Door Dilemma — which is simply an approach to decode these subtle conceptual differences. And once we do decode them, we can gradually move toward a more precise way to express what’s on our mind™ — which, in turn, should help us build our ad hoc concepts with improved precision. Let’s take a look at an example illustration:

Ad Hoc Privacy

Fig. 9 depicts one possible situation: at least one of us is aware of the nuance illustrated in the Locked Door Dilemma. Applied to our verbal exchange, this time you’d be equipped to point out the subtle change of topic introduced by my reply. As a consequence, you can help us both build an ad hoc definition of privacy that is a little more precise, starting by pointing out that nothing to hide belongs to secrecy. This will lead to the next question: how could we approach privacy? Something to think about.

Now, since we have figured out that we should pay closer attention to nuance, it looks like we’re on our path to building Natural Language 2.0 with the following release note:

what’s clogging up our mind™

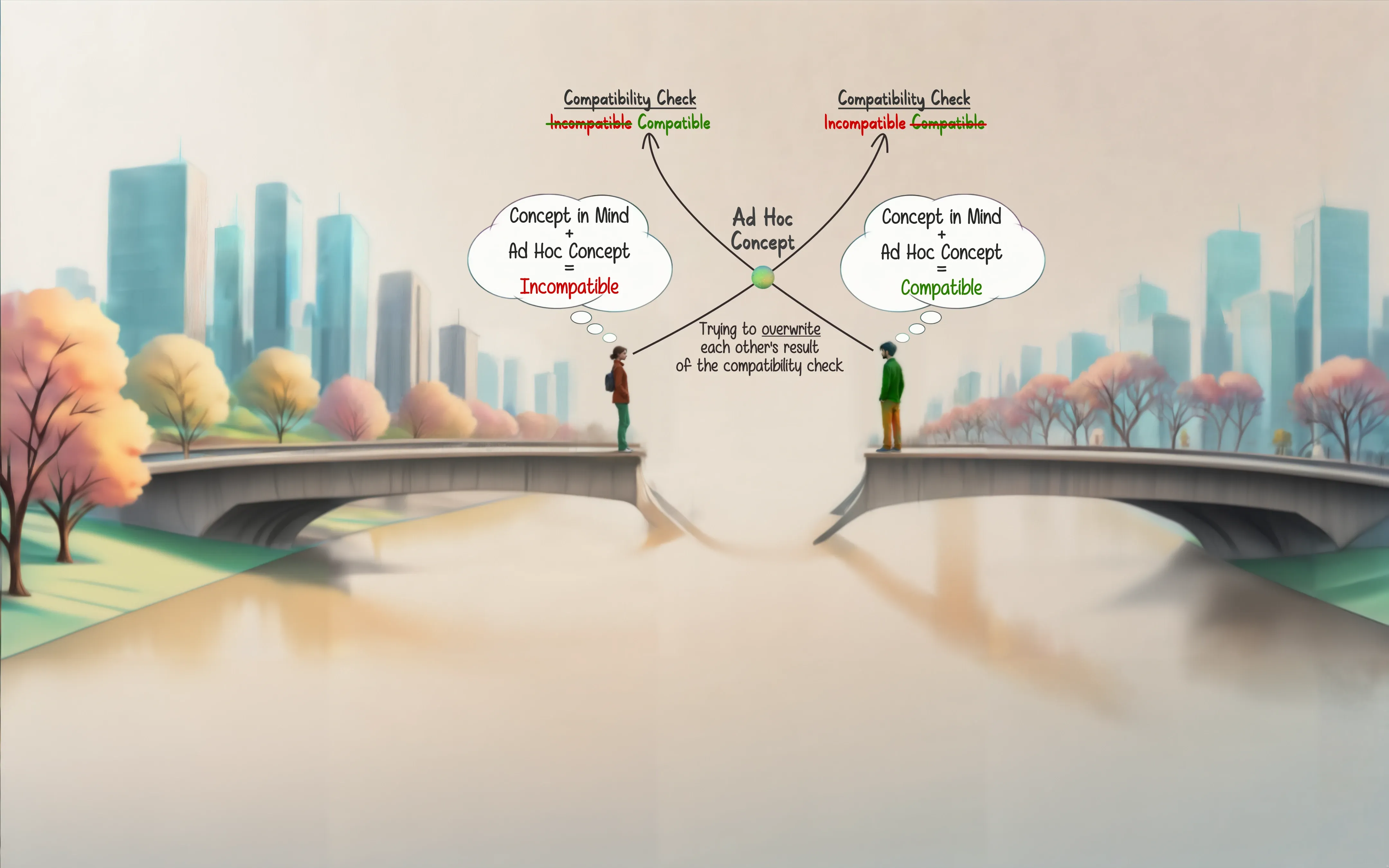

Well, at the time of writing, the situation depicted in Fig. 9 isn’t particularly common in my neck of the woods. While no one engaging in a verbal exchange can be excluded from favoring an invasive approach — peppered with emotion — to propagating meaning, it is especially our public discourse that is in a constant battle for ownership of ad hoc meaning. After all, controlling ad hoc meaning can be used as a proxy to overwrite other peoples’ (conceptual) understanding. In other words, linguistic precision seems like a bit of an afterthought:

Ad Hoc Meaning as a Battlefield

Fig. 10 can easily be summarized with words such as persuasion, but it is a little more than that. It is an attempt to successfully convey what’s on our mind™ — and by successfully I mean: if we express the same concepts with the same words, we are more likely to assume that we understand them in the same way. However, simply building concepts with the same words isn’t a guarantee for linguistic precision. Think about it: if both of us are using nothing to hide as a building block for privacy, we have established a common ground, but our language still has secrecy as a more precise fit for nothing to hide. In other words, there’s a missed opportunity for improved precision. This leads us to having a hard time deciding whether going to the bathroom pertains to a basic human need or a potential crime. And that’s just one example.

All things considered, it is very difficult or practically impossible to determine whether we face linguistic precision or the illusion of it. To be honest, though, I hope that by the end of this piece you’ll entertain the possibility that it doesn’t matter whether precision is illusionary or not. After all, the results obtained from negotiating ad hoc meanings always matter within their specific context — and sometimes even beyond.

That said, based on the comparison of Fig. 10 and Fig. 9, I suggest the following conclusion: the less nuanced our linguistic awareness, the more likely we end up with a situation as depicted in Fig. 10. Instead of a collaborative effort to improve linguistic precision, we end up with a competitive effort to overwrite our fellow human beings’ perception according to our own. This can be expressed as linguistic correctness: an authoritative approach to tell other people how they are supposed to express themselves — and, as a consequence, to suppress themselves.

Of course, it is important to emphasize that the invasive approach depicted in Fig. 10 doesn’t have to be motivated by a desire to rewire other people’s views to benefit our own. Rather, often times it is the only approach we can think of to try and improve the linguistic precision needed to unclog our mind™. It definitely has the potential to be quicker than negotiating an ad hoc meaning — but at what cost? Well, one possible outcome could be that we end up with sameness rather than precision.

Linguistic Precision

One of the reasons we face a non-negligible lack of linguistic precision is that our languages’ evolutionary trajectory is confronted by myriad influences from all sides — all the time. Understandably, this can leave quite a bit of a mess behind. But that’s only one half of that particular reason — the other one being that we don’t seem to be spending an awful lot of time trying to clean up that mess. Sure, we often play with the resulting imprecision and there have been certain attempts to control what can be codified into a natural language, but if we’re honest with ourselves…that’s nothing but a fool’s errand, a Sisyphean (opens in a new tab) task. And as mentioned above: same goes for blindly propagating our own building blocks.

Personally, I don’t think that all this linguistic imprecision has anything to do with us not caring enough about the issue. Rather, the problem is that up to the introduction of a global communication system not that long ago, the mess left behind on our languages’ evolutionary path wasn’t that obvious. At least not to most of us.

Of course, some of us have been trying to make sense of it — and likely succeeded in unraveling a large chunk of the mysteries beneath the surface of our expressive systems. I dunno. I just like to entertain the possibility. But hold on! If that’s the case, you might wonder, why aren’t we all in possession of these great insights? Well, I guess they either resurfaced with the results expressed in words that not many of us could meaningfully put together — or if we could, we didn’t bother passing the torch on to someone else. Or maybe, after making sense of it all, they were unable to resurface and, as a consequence, left to deal with psychological troubles. That is especially the case when it comes to the frustrations related to an inability to express what’s on our mind™ — or fail to establish compatibility with others. After all, it ain’t fun to be a prisoner of your own mind™ without a connection to the outside — leading to feelings of isolation and other challenges. At least in our current state.

On the flip side, most of us just keep chugging along without a second thought. I mean, what else is there to do? Then again, times are changing. And they remain the same. They always are, they always do. Welcome to the joys of thinking in contradictions.

Now, unlike being trapped inside of our own head, our growing linguistic mess doesn’t keep us from moving forward. It just forces us to take a couple of detours and to remove a few obstacles to reach some common ground. Once we do, we hopefully stop moving in circles chasing our own tail — which leads us to the first step of the cleanup: to verbalize or encode it into our language. Gives us something to work with. To that effect, I’d like to offer what I’m going to call a flawed proposal: something I can suggest to the best of my expressive abilities in this particular moment, knowing full well that it requires more work.

We could, for instance, build a common denominator that will tease out whatever linguistic building blocks we are able to produce in relation to that common denominator. In plain English: I could show you an expressive puzzle and ask you to simply describe in words how you would solve it. One prediction that I’m comfortable with is that no two people will produce the exact same building blocks in the exact same constellation for their solution.

Traditionally, that would lead us to conclusions such as everything is subjective, just a matter of perception or something resembling concepts such as relativism (opens in a new tab). I guess. I dunno. I don’t really understand these things. As I mentioned at the beginning, I’m not interested in philosophizing about the nature and meaning of anything and everything. My concern lies more with the question: how can we develop and connect different approaches to building a common ad hoc concept that will benefit us all when it comes to improving linguistic precision? Because as far as I’m concerned, it ain’t about subjective or objective realities (I don’t even know how to build these concepts in a meaningful way), but about our ability to negotiate precision — both with ourselves and one another. Ideally, this will lead us to express what’s on our mind™ with improved precision.

Playstyles

Consider the following illustration:

The Pigeon Conundrum

At the beginning of this piece, I told you that this is an invitation to play a game. A linguistic one to be precise. The question: how are we supposed to play? This is where Fig. 11 comes in. Essentially, the Pigeon Conundrum is what I’m going to call a playstyle generator. Here’s how it works: I ask people how they would approach the conundrum and their answers can be used as playstyles to decode linguistic nuances.

A couple of things to consider before I share the list of playstyles: value judgments regarding my participants’ answers are absolutely useless to me. One important nuance to understand is that my label linguistic precision has nothing to do with what we might call some sort of correctness — as should be obvious by now and, again, as mentioned in the first few lines of this piece: there’s nothing prescriptive about this endeavor.

The point isn’t to be told what can be done and what rules to follow, but simply to do something and question it as we go along. And that means no shortcuts! There’s no way that we could outsource this challenge to something like a computer — not because it wouldn’t be able to overcome the challenge (it probably would), but because its success isn’t directly transferable to us. In other words: we cannot completely avoid having to make a somewhat demanding effort. But for what it’s worth: I think that no matter the direction it is going to take us in, we won’t be disappointed with our potential discoveries. I mean, expressive systems such as natural languages are a playground waiting to be discovered, right? I’m just putting a couple of makeshift tools together to get the exploration started. The rest will have to be figured out after this piece of writing.

With that in mind™, every participant was shown the original Pigeon Conundrum and simply asked the question:

How would you approach this challenge?

Here is our list of about a dozen playstyles I managed to gather in a reasonable amount of time.

Participant A

Participant B

Participant C

Participant D

Participant E

Participant F

Participant G

Participant H

Participant I

Participant J

Participant K

Unsurprisingly, the answers — or playstyles — are quite different. Question is: how and where can we apply these playstyles? Well, that really is up to us and what we want to discover. I guess what I’m saying is that we are going to need a pinch of creativity to move forward. In my case, I’m going to pick one or two of these playstyles and try to make sense of this piece of writing. Seems a bit meta, but that’s not my intention. It’s just that I have no clue what I’m doing. I know…you’ve probably figured that out a long time ago. Thank you for indulging me.

Now, where was I? Ah yes…if you’re cool, I’d say we continue using some of these playstyles as a compass to keep exploring and find out where they take us.

Take Participant B’s first proposed playstyle:

The pigeon can be anything I guess. It’s like a referent (opens in a new tab).

Within the context of this piece, I assume the pigeon could also be replaced with awareness. After all, according to this participant, anything goes. I like it. By extension, we could even replace awareness with the pigeon. But why would we do that? And really: awareness is not a pigeon, is it?!

Well, it kind of is, but I’d express it as follows: once awareness and pigeon exist within the same context — such as natural language — they are interchangeable. As a matter of fact, so is what you see on Fig. 11 — even though the specific context is different as it is a visual representation and not just words such as pigeon or awareness.

Zooming out, visual representations and words belong to the same context: they’re part of an expressive system. In a away, The Treachery of Images (opens in a new tab) is a good example to highlight the boundaries between these different expressive systems. Essentially, all we’re trying to do here is to remove these boundaries and see whether we can use different expressive systems (or components thereof) such as words and visual representations interchangeably to help us find ways to better understand how we can and do engineer meaning. In a nutshell: these different expressive systems have (at least) one common denominator: they all can be carriers of meaning — so why not use them interchangeably to paint a more detailed picture?

I want to start by replacing awareness with the representation of a pigeon from Fig. 11 and see where that takes us:

Lost in Translation

There’s a lot going on here — starting by combining two expressive systems: visual representations and natural language. Of course, avid comic book readers would want to have a word: So what? Big deal!

Well, in Fig. 12 these two expressive systems aren’t simply there to complement each other, but to interact and merge to a certain degree. In doing so, we can start visualizing what might happen to abstract concepts — such as awareness — during a verbal exchange. In a nutshell, words without a visual representation might become a little more tangible.

The first step: the person on the left visualizes and describes a pigeon (specific) and the one on the right uses that description and ends up visualizing a bird (generic) as he doesn’t have a specific representation of what a pigeon is — at least not the representation of a pigeon the person on the left has. The man, however, has an understanding of its features and can put them together to form something that is good enough to connect the bridge between them. I guess they’re having a verbal exchange without trying to kill each other.

The second step: establish a continuum with specific pointing in one direction and generic in the opposite one. Their mission: to calibrate their individual conceptual understanding of awareness on that continuum so that their ad hoc definition of awareness is slowly moving in the direction of specific. The reason? Because, just as with the pigeon, the man on the right doesn’t have a specific understanding of the conceptual understanding of awareness the woman on the left has — nor does the woman have an understanding of the one the man has. And this is where the expressive systems of our choice matter.

Using words alone, we often tend to produce a whole lot more of them when we want to reduce complexity. Incidentally, an aphorism (opens in a new tab) would be a good example for the opposite: we pack conceptual complexity into as few words as possible without reducing the complexity itself. Instead, we let the recipient deal with unpacking that linguistic box and assembling the content. Basically, the more we reduce the reading time, the more we increase the thinking time. However, increasing the reading time doesn’t serve as a guarantee for reducing the thinking time. That’s a bit unfortunate, but nothing that should stop us in our tracks.

By contrast, when using visual representations in addition to words, we can reduce complexity by modifying our visual representations and, in the process, avoid having to increase our word count. The cool thing about this approach is that tweaking a visual representation doesn’t require the person seeing it to spend more time looking at it — as it would require a reader to spend more time with a text the more words it contains. The point is: instead of substituting one expressive system for another and thus changing the context to express the same idea in a different way (e.g. your typical metaphor (opens in a new tab)), we could make these different expressive systems coexist in the same context and make them interact with each other. In summary, we could produce slightly enhanced metaphors such as Fig. 12.

That being said, Fig. 12 obviously simplifies a lot by assuming a fairly convenient common ground to begin with — not to mention that I should probably start fiddling around with things like the Peripatetic axiom (opens in a new tab). Fortunately for me, though, I’m not a philosopher so I won’t bother. Instead, let’s re-evaluate: we’re not just trying to solve a puzzle, but we are simultaneously creating it. This forces us to consider two different approaches at the same time: solving a puzzle requires us to put the pieces back together in order to complete a whole — creating one, on the other hand, requires us to decompose that completeness. In other words, Fig. 12 is a bit like reverse engineering a solution into a problem and putting it back together in a slightly modified but still compatible way — and thus having the potential to open up different perspectives while keeping a common (or at least familiar) ground.

Finally, I want to go back to precision leakage. Every conversion related to an expressive system such as mind™ -content-to-natural-language or sensory-to-natural-language (and possible reverse directions) will leak precision that we have to make up for somehow. For instance, an actual pigeon and its representation in our memory are not identical — neither is a drawing nor a photograph. Depending on the type of conversion, we lose more or less precision and have to make up for it with more or less effort. In short: describing something with a visual referent will probably be easier than something abstract like a concept — leading us to replacing the representation of the pigeon with awareness:

Blind Awareness

With Fig. 13, we’re at the intersection of Participant B’s and Participant E’s playstyles — the latter proposing the following one:

I’d say it is impossible or difficult to communicate if we don’t see the same thing. We probably would have to adopt a different perspective. But how?

Of course, we could argue that Fig. 13 shows us both seeing the same thing: nothing. I guess it’s a good thing, then, that nothing is such a simple concept that we can be certain to use the exact same linguistic building blocks to make sense of it. Right?

Two things: by now, we should have a hint for Participant E’s question and an explanation for why it might appear to be impossible to communicate if we don’t see the same thing.

The hint lies in Participant B’s approach to decouple the pigeon from its representation so we can replace it with whatever we feel like. This is something we’re allowed to do because we can. It’s that simple.

So while Participant E uses a strictly descriptive approach to the pigeon conundrum, pointing out that we would have to adopt a different perspective and leaving it at that, Participant B immediately picks one building block (representation of the pigeon) and suggests to change that particular perspective. Of note is that these two participants don’t know each other and — as far as I know — have never met. However, within the context of the pigeon conundrum, they might be ideal conversation partners as their approaches seem to be complementary. What does that mean for the rest of us? Dunno about you, but I’d be curious to learn from them.

Which brings me back to Fig. 12: it is indeed difficult to communicate if we don’t see the same thing, but it doesn’t have to be impossible. Once we figure out how to change the perspective, it all depends on the required level of precision for a given verbal exchange followed by optimizing for that level of precision. Essentially, the idea is to apply what happens in Fig 12 with a visual referent i.e. the pigeon-to-bird-precision-leakage to an abstract concept such as awareness in Fig. 13. Again, combing visual metaphors or, in this case, different expressive systems won’t magically reduce complexity, but it can make it more apparent. In other words, being aware of precision leakage when discussing concepts, we can take steps to mitigate that leakage. And one reason to make that extra effort is obviously to avoid misunderstandings — or to build a proper foundation for a (linguistic) common ground.

Fig. 13, on the other hand, can serve as an explanation for why we might think that something is impossible to communicate. Taking a wild guess here, but I’d say that changing the perspective alone isn’t good enough. After all, we have all sorts of tools such as metaphors, similes, allegories and so on enabling us to change the perspective, but I wouldn’t say that they are a guarantee to communicate previously impossible or difficult to communicate ideas. For one, we stay within the same expressive system to trigger a different one in thought. In plain English: I’m using words to make you visualize something — and whatever you end up visualizing isn’t visible to me. This makes it extremely difficult to account for the resulting precision leakage and the required effort to make up for it. On top of that, nothing prevents us from taking figurative components literally. And once that happens, we’ve basically engineered ourselves into our own prison of the mind™ — as depicted in Fig. 13.

You see, Fig. 13 isn’t a puzzle, but an illustration for the limits of an expressive system: natural language. There’s no way to think our way out of this because our chosen communication tool isn’t compatible with the context we’re in. In other words, two people without the ability to see won’t be able to combine words with a visual referent to shine a light on abstract words. They are trapped inside an abstraction — a place so dark that all of us are equally blind.

That being said, the conundrum depicted in Fig. 13 isn’t a result of our natural language’s evolution. After all, our species wouldn’t have been able to evolve our natural language’s current form without the ability to see. Don’t get me wrong, though. I’m not suggesting that a blind species isn’t capable of communicating, just that such a species would develop their communication system optimized for their abilities instead. And that is what makes the attempt to solve the conundrum depicted in Fig. 13 such a waste of time: it isn’t meant to be solved as it retroactively tries to fit a situation that would have made it impossible to evolve our language into what it is today.

So what’s next? A dead end isn’t the end of the journey — just a reminder to look elsewhere for a way forward. Or as Participant E suggests: we could change the perspective. For instance, how about tweaking the situation depicted in Fig. 13 to make it a little more specific. In other words, two completely blind people won’t be able to visually describe what they cannot see, but how about something a little less extreme?

Expressive Imprecision

So far, using Participant B’s proposed playstyle, we have explored two options with Fig. 12 and Fig. 13 — the former leading us to visualize precision leakage when communicating abstract concepts and the latter leading us to a dead end.

In order to get out of that dead end, we can use Participant E’s suggested playstyle to change the perspective. So instead of depicting a state where we don’t see anything at all, we could consider one where we see at least something — or everything imaginable but something. Like color. Well, how about being colorblind?

When applying that particular change of perspective to this piece of writing, we can, for instance, highlight a fraction of the imprecision that I’ve simply accepted as a trade-off to be able start this endeavor in the first place:

What's the Difference?

Before attempting to solve this little puzzle, I’d like to briefly discuss Fig. 14 in relation to Fig. 1 and Fig. 13.

Codifying different nuances of meaning in color as I’ve done with Fig. 1 is probably not a good idea when attempting to explain this to someone who cannot see color. That’s fine, though, as I never intended to uncover some sort of universal truth (opens in a new tab) allowing me to provide an answer tailored for every imaginable mind™. Again, I don’t even understand what that means. It looks somewhat static to me. There’s nothing to negotiate — just my perspective.

You see, by defining meaning in a static way, our ad hoc world can only be a static one — as it is now. One that will always be in conflict with the dynamic nature of ourselves and the context we’re born into. This will keep producing contradictions for those of us who explore the boundaries of an expressive system. At times, these contradictions seem like an existential dead end rather than innocent indicators pointing out the limits of said expressive system. And by the way: limits that don’t need to be explained. As a matter of fact, they cannot be explained. But feel free to give it a go. At the very least, you’ll be producing playstyles — and that is probably a good start toward dynamically defining meaning.

Basically, the paradox as a playstyle generator as depicted in Fig. 13 has the potential to produce an infinite amount of playstyles. The problem: in actuality, it is just one playstyle simply dressed in different words. Its boundaries become apparent as soon as we start being meta about being meta about being meta (opens in a new tab). In a way, that is a bit ironic given that infinity in a statically defined context of meaning is a paradox itself. Talk about going in circles…

Welcome to expressive imprecision: let’s substitute words without a precise definition for words without a precise definition — with the former being yours and the latter being mine. Oh my god! Did you see that big bang?! Really, though, what are we trying to accomplish here? Multiplying imprecision with imprecision to move toward precision?

Congratulations! We are trapped and prone to a competitive approach to defining meaning — with everyone of us worried about coming out on top of the hierarchy. There are plenty of examples, especially revolving around the concepts of creation, beginning and end. Seems a bit like an explosive mix to me. Then again, I don’t understand these concepts. Playstyles without an appropriate game? Or maybe not a lot of us ready to play, yet…

Of course, the disadvantage of dynamic meaning is that it would turn our current ad hoc world upside down. But what really sucks is that we can forget about the notion of a representative thinker. Or think of it this way: if we don’t do it ourselves, no one can do it on our behalf. That’s cool as long as we are cozy in our static ad hoc world, but I have a feeling that it will get increasingly boring in here — and we’re slowly running out of distractions. Well, I guess it’s time to solve Fig. 14:

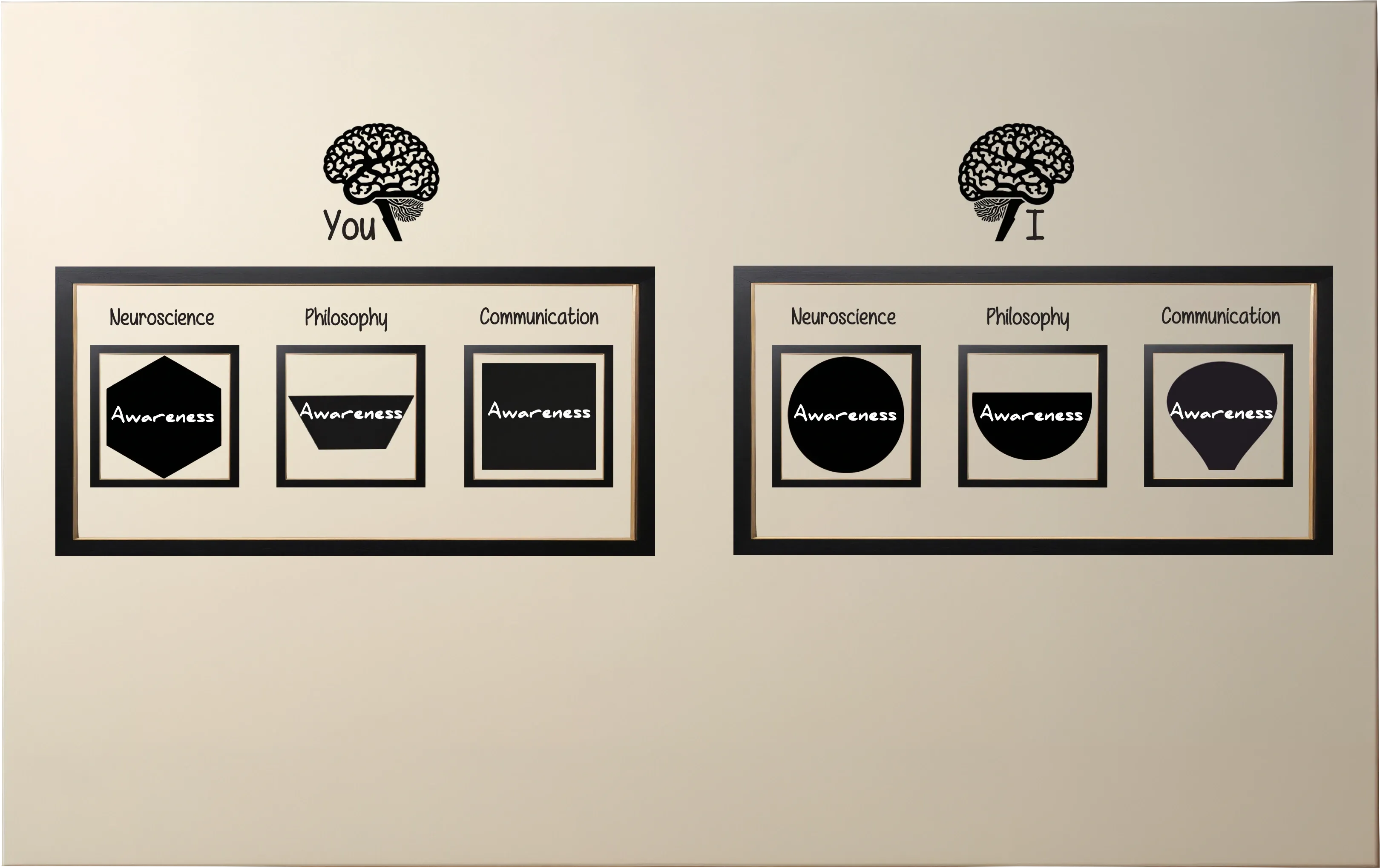

Codifying Nuances of Meaning in Shapes

I guess color blindness shouldn’t be a problem anymore when it comes to seeing that there are six instances of awareness and none of them have the exact same meaning. Or maybe? Well, using shapes instead of color to codify nuances of meaning seems rather obvious if we can’t see color, doesn’t it? Come to think of it, I could’ve also used different fonts. But let’s not go there. Thank you.

Now, you might wonder: shouldn’t Neuroscience, Philosophy and Communication be framed in different shapes (or colors) as well? After all, they’re probably not exactly the same either — depending on whether the perspective is yours or mine. And of course, You and I are obviously different, making it clear that the context isn’t the same, right?

First, the reason I didn’t bother with tagging the categories depending on whether the perspective is You or I is because I wanted to highlight awareness — and because this piece is full of shortcuts so I can convey a thought without having to solve a mathematical equation before every word I produce.

Thing is, as humans we love to point out imprecision in an effort to protect the status quo of our personal mind™ space — and that is fine. Think of it like our natural language having its own immune system protecting our sense of self from being shred to pieces by foreign concepts, ideas and so on. We first need to build up some resistance to meaningfully integrate these foreign things into our mind™ space — making them our own. As long as we cannot, we’re in attack mode. This can manifest itself by pointing out imprecision:

But your solution doesn’t fully explain this and that.

Here’s some food for thought: an incomplete solution (or the lack of one) to a problem doesn’t make the problem less of a problem. I get it, however, we are only ready to move on if we can solve the problem of uncertainty first. Too bad, then, that often times uncertainty persists as long as we dwell in the status quo. Sometimes, there’s just no other way than to cut our losses.

As for the question whether You and I are different, here’s what Participant A’s proposed playstyle based on Fig. 11 has to say:

Difficult to define who you and I are.

Why is that? We could assume that, as the author, I refer to myself with I — and I guess that makes You you?

Well, I didn’t provide any context to these participants other than asking them how they would approach the conundrum. That leaves them to define these words based on the perspective they choose. For instance, Participant D takes I and assigns You to me:

The picture shows a situation where I see something and you don’t.

By contrast, Participant B chooses a different perspective:

I don’t know what you see and have to figure out how you would communicate this information?

Holy shit! If that ain’t confusing, I don’t know what it is. What’s going on? Here I am, trying to have fun writing this piece and — from the looks of it — I’ll end up getting crushed by an identity crisis.

A thought: if we try to squeeze our sense of self — which is dynamic — into a single linguistic unit such as I or You — which is static — we’ll run into an existential crisis sooner or later. Unfortunately, in our static ad hoc world, that’s our only option. Essentially, we hop between linguistic components constantly trying to catch up — doomed to never be fast enough. That’s why I’m probably a writer? But why? Sometimes I drink coffee. Am I a coffee drinker then? What about when I go for a walk? A hiker? Or maybe I am my job — but that makes it impossible to define myself when I’m in between jobs?! Well, better start drinking coffee so I’m at least a coffee drinker again. Ahh! I can’t keep this up anymore…I guess we’re back at the Sisyphean (opens in a new tab) task. If you have an idea how to capture something that constantly evolves using a tool that produces static results, I’m all ears.

Of course, it is important to keep in mind™ that we’ve engineered ourselves into this mess not because we’re a bunch of idiots, but because in order to become aware we gotta experience first. And no, I’m not talking about experimenting with drugs. If we want to take on language, we better get our shit together — because when those building blocks come crashing down…we are screwed. I mean…I is. Or You? Alright, enough!

Conclusion

I want to use these final words to highlight the most important aspect of this piece: I am simply playing a game with language, using humanly generated playstyles to define and change the rules in order to fine-tune linguistic precision — or at least the illusion of it.

Fact of the matter is, we’re trapped inside of our language. In other words, we’re mostly using a hammer to hammer a hammer. How about we start looking for nails instead? If we can’t find them, we can always imagine them. After all, the hammer in question is imaginary as well.

Of course, the goal is not to redefine every word in existence or to create new ones to house meaning that we were incapable of fitting into already existing words. They are words — and they are not affected by concepts such as new and old. Instead, I suggest to slowly move away from static meaning. Our next objective could be to learn how and when to reverse engineer carriers of meaning to bridge conceptual gaps in our understanding. In short, scattering imprecise meaning over more words is probably not going to make things less confusing.

To that effect, a collaborative effort in building ad hoc meaning could help us to express ourselves with improved precision. Obviously, it is important to emphasize that an improved precision doesn’t lead us to being in agreement with everything. I mean, we’re not a bunch of hippies anymore trying to spread love, are we? The goal is to better understand when and why we agree or disagree with one another. This, in turn, will help us decide to what extent it is possible to dwell in a shared ad hoc mind™ space without killing each other. We’re not all meant to be neighbors, after all.

By contrast, a competitive approach does in fact aim for us to be in agreement with everything. Back to being hippies spreading love, I guess. In all seriousness, though, whatever the concept and how we feel about it (good, bad or anything in between), the process remains the same: invading and colonizing other people’s mind™ space through ad hoc meaning. In plain English, everything would be better if everyone shared my view. And as we could see in the previous section: depending on the perspective, we might have a problem defining whose view that is. I’m sure you tend to call yourself I as well, don’t you? In a nutshell, overwriting the results of our compatibility check could end up contributing to an increased mess on our languages’ evolutionary trajectory. And on top of that, we’d be forced neighbors — in prison cells of our own design.

Finally, this game doesn’t allow for spectators: as soon you as you’re exposed to it, you play. I dunno about you, but in that case, I think we might as well have some fun participating.